estratègica regió saudí xií

Shiites reel from attack in Saudi province

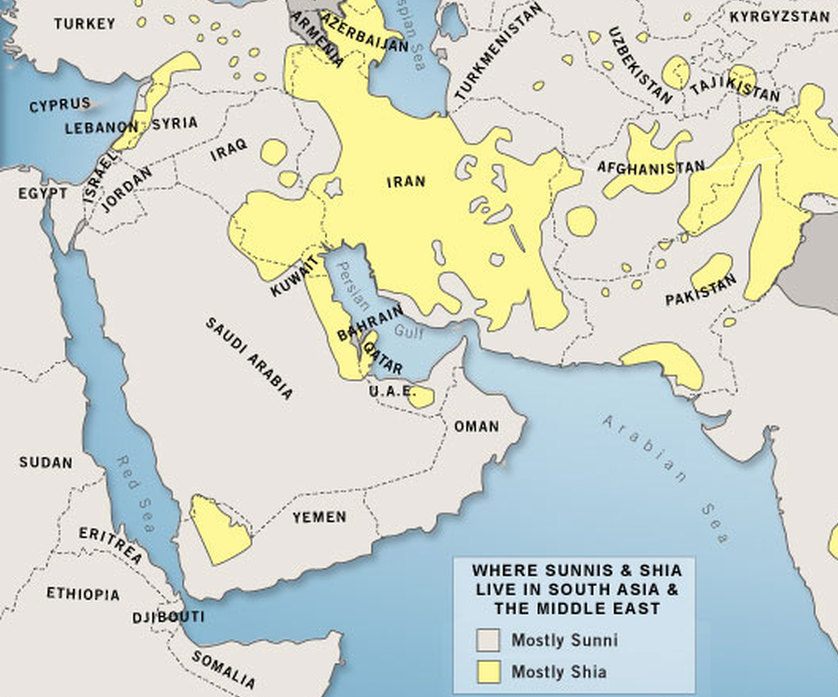

The Shiite community in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province suffered an unprecedented attack May 22, as the Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing during prayer in the Ali bin Abi Talib Shiite mosque in al-Qudaih, a village near Qatif, a predominantly Shiite town associated with a high level of Shiite dissidence, activism and demonstrations.

Saudi authorities named the perpetrator as Salih al-Qashami, an alleged member of an IS secret cell and one of 26 men on the latest Saudi list of wanted radical suspects. The bombing resulted in more than 20 deaths and multiple injuries.

At another level, an unprecedented solidarity campaign with the victims immediately began to surface, with the leadership and society condemning the attacks and calling for national unity against those who undermine peace and harmony. The great irony is that the IS attack stems from the convergence of state systematic discrimination against the Shiites, the unwillingness of the latter to curb the excesses of Wahhabi denunciation against them as heretics and untrustworthy fifth columnists, and the de facto support for the ideology of IS in Saudi society.

The Shiite community is in mourning; its activists and dissidents at home and abroad are understandably furious and shocked by the outrageous attack. Violence in sacred spaces is no longer a new phenomenon in the Arab world. Saudi Arabia itself had seen one such attack on a Shiite mosque in Dalwah, killing several people during prayers a couple of months ago.

Prominent exiled veteran Shiite activists such as Hamza al-Hassan and Fuad Ibrahim clearly regard the May 22 attack as a product of years of cumulative denunciation of Shiites, pejoratively referred to in Saudi religious texts and popular media as "rejectionists," Iranian clients and a treacherous fifth column. In several tweets immediately after the attack, Hassan asserted that IS, known in Arabic as Daesh, is "made in Saudi Arabia," a reference to the identical ideological roots of IS and Wahhabi Islam (@hamzaalhassan). He saw no real difference between the two movements when it comes to condemnation of Shiites and their rejection as true Muslims.

Prominent exiled veteran Shiite activists such as Hamza al-Hassan and Fuad Ibrahim clearly regard the May 22 attack as a product of years of cumulative denunciation of Shiites, pejoratively referred to in Saudi religious texts and popular media as "rejectionists," Iranian clients and a treacherous fifth column. In several tweets immediately after the attack, Hassan asserted that IS, known in Arabic as Daesh, is "made in Saudi Arabia," a reference to the identical ideological roots of IS and Wahhabi Islam (@hamzaalhassan). He saw no real difference between the two movements when it comes to condemnation of Shiites and their rejection as true Muslims.

Ibrahim, who's more academically grounded in his writings on Shiite history and jurisprudence, retrieved the multiple damming Wahhabi religious edicts from the 19th century and reminded his followers of the names of the great founding fathers of Wahhabi prejudice against Shiites (@fuadibrahim). Younger Shiite activists explored the Internet and retrieved statements of current Saudi clerics against the Shiites and recirculated them online, thus implying that those who are now condemning the attack were only yesterday propagating hate speech against them.

Tawfiq al-Saif, another of Hassan and Ibrahim's veteran Shiite comrade who returned to Saudi Arabia from his exile in London following a reconciliation with the regime in 1993 during the reign of King Fahd bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud, reiterated his demand to issue a royal decree criminalizing hate speech and violence.

On his Facebook page, he wrote an emotional letter of condolence to his co-religionists, promising great solidarity and persistence in adhering to the spirit of Shiite Islam, and reminding them of several revered ancient Shiite symbolic figures, including Hussein, the slain grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. Addressing the perpetrators and their supporters, he invoked the infamous pagan Abu Lahab, determined to kill the early Muslims who responded to the prophet’s call in seventh century Mecca. He addressed the criminals who attacked the mosque as "the heirs of Abu Lahab" and indicated that they will burn in their own fire.

However, the most important message was reserved for the leadership, reprimanding it for delaying a law that criminalizes hate speech and punishes the many clerics and others who propagate poisonous opinions against Shiites. Saif held the Saudi leadership responsible for not protecting Shiites and for their slain worshippers. He called for immediate equality between citizens, in which both Shiites and the martyrs of such recurrent terrorist attacks are considered worthy full citizens, like others who died in previous radical attacks from among the Sunni majority.

Saif chastises Saudi intellectuals, activists and religious scholars for descending into sectarian hate speech, especially in the last months, and enlisting a wide pool of followers to propagate hate against Shiites. It should be noted that Saif’s diagnosis of the position of many Saudi activists, locally known as harakiyyin — a reference mainly to Sunni Islamists — on Shiites is accurate. With Operation Decisive Storm, many Saudi Islamists who may have had reservations about the leadership’s handling of the Arab uprisings, especially in Egypt, promptly did an about-face to glorify their leaders' military strikes on Yemen, constructed as putting an end to both Shiite empowerment in the Arab world and Iran’s predatory expansion.

While many Saudis are implicated in propagating hate speech, Islamist Sheikh Salman al-Awdah has never been a persistent propagator. He, like many Sunnis and Salafis, would not hesitate to call the Shiite rejectionists, but his arguments tend to be more nuanced. After 9/11, he participated in one session of the government-sponsored National Dialogue Forum in which discussion was centered on national unity against radicals.

Awdah was one of the first Saudi scholars to meet Hassan al-Safar, a Shiite cleric who had led the Shiite opposition movement from Syria in the 1980s but reconciled with the government and returned to Saudi Arabia together with Saif and others. Awdah distinguishes between the theological differences between the Sunnis and the Shiites, considered seriously insurmountable, and current political positions. He called for acceptance of the Shiites as a minority in Saudi Arabia that should enjoy full recognition and equality, but he rejects the politicization of Shiite identity, seeing it as the basis of which sectarianism can flourish and threaten the unity of Muslims. After the May 22 attack, Awdah appeared on Al Jazeera Arabic TV, offered his condolences, and called for treating the Shiite question as a domestic issue pertinent to the Saudi domestic context rather than linking it to regional sectarian conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. His tone was reconciliatory, sympathetic and worried about the aftermath of such a dreadful attack on innocent worshippers.

Other Saudis expressed horror over the attack, calling for an end to hate speech and ideological and sectarian polarization. Prominent among them is a circle of human rights activists and lawyers such as Ibrahim al-Mudaimigh, known for his work on the cases of detained Saudi civil and political rights activists, and journalists and writers in the local Saudi media.

The fear that such an attack would probably lead to further terrorism against the Shiites, thus leading to serious Sunni-Shiite confrontations akin to those that dominate Iraq and Syria, must be real and frightening to everybody in Saudi Arabia. The leadership is currently overwhelmed by an external war in Yemen that has not brought a desired outcome. It has yet to respond with a program of reconciliation with the local Shiites, to offer serious improvement in the Shiite life conditions to criminalize hate speech, honor Shiite victims and compensate their relatives as it often does when the victims of terrorism are Sunnis. This is not to mention its five-star rehabilitation program that offers repented radicals a great salary, a wife and a job. The visit of the governor of the Eastern Province, Prince Saud bin Nayef, to the local hospital treating the Shiite injured, the grand mufti’s condemnation of terrorism and official press solidarity rhetoric may prove to be short-lived, expedient reactions to a deep crisis.

National solidarity rhetoric and poetic condolences will no doubt fall on deaf Shiite ears when the security forces of Mohammed bin Nayef, the interior minister and crown prince, continue their occasional raids on Qatif in search of alleged dissidents, fire at peaceful demonstrations and kill many Shiites. The death toll among young Shiite activists is more than 20 since 2011. From the Shiite perspective, there may not be such great difference between such raids and the occasional deadly terrorist attack.

With such recurrent attacks, we cannot rule out that the Shiites may never consider creating local brigades similar to the Iraqi militia known as Hashid Shaabi, to protect Shiite towns in the Eastern Province. However, the Saudi Shiites may not want and may not have such a solution readily available as they live in a country where the state is much more in control of its population and territory, at least at the moment. Moreover, the Saudi Shiites are short of a foreign patron who can arm them like the Iraqi state and Iran arm their recently created militia.

Saudi Shiites are a small minority in a country that continues to remain hostile to their religious tradition, rituals and loyalty to clerics beyond Saudi borders. Most of their activism since the 1960s has been peaceful, with occasional violence erupting mostly by the security forces. Since the Arab uprisings, they have remained peaceful, calling for citizenship and respect for their differences. However, if the leadership continues to ignore such demands in a region where sectarian violence is the language of politics, the situation will continue to deteriorate. The Saudi leadership better listen to the demands of a battered minority before it is too late.